Definitions:

Complex Trauma & Dissociation

What Is Complex Trauma?

Many people are familiar with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. A hard or “bad” thing happens, it’s a one time thing, and it’s over. Then a person experiences symptoms in response to that traumatic experience “post-trauma”. This is part of the brain trying to heal.

However, complex trauma is chronic, relational, and ongoing. CPTSD happens when painful or unsafe experiences occur over and over, especially in relationships where we should have been protected. That piece is key: it’s not just the hard or bad things that happen (trauma), but also the good that was missing (deprivation). Instead of a single event like with PTSD, it’s an ongoing pattern (chronic neglect, emotional abuse, betrayal) and often beginning in childhood.

Because the danger comes from people we depend on, the mind and body learn to survive in ways that make sense in those moments but can be confusing later.

Complex trauma is not just about what happened. It’s about what kept happening, and what never happened that should have been happening all along: safety, care, and connection.

It shapes how we see ourselves, others, and the world. And it’s in this context that dissociation begins… not as a disorder, but as a brilliant survival strategy.

What Is Dissociation

Dissociative capacity is the brain’s way of keeping us safe when the world isn’t. It’s the brain’s way of keeping us safe when the world isn’t. When experiences of harm, betrayal, or deprivation overwhelm our ability to cope, or when we have to maintain attachment with abusive, absent, or depriving caregivers, the mind learns to separate from what one is experiencing in order to survive.

Why Dissociation Happens

Our minds are designed to protect us. When there’s danger, the body goes into survival mode: flight, fight, freeze, or fawn.

We can imagine that flight is getting away from the tiger, and fight is trying to overcome the tiger. In the same way, “freeze” is the neurobiological response of not moving so maybe the tiger will just pass by. Fawning is also a dissociative response, as if feeding the tiger will keep it from eating me. These freeze responses can happen when we cannot escape the danger, cannot win against it, and either must wait it out or endure it (such as children who need their caregivers to survive, even if their caregivers are the danger through trauma or deprivation).

We see this in Betrayal Trauma, when the very people we depended on for safety were also the ones causing harm. In these experiences, our system had to find a way to stay attached and survive at the same time. Some parts of us held the pain or fear, while others stayed connected to the people we needed. This separation allowed love and terror to coexist, even when that was impossible on the outside.

We also see this with Developmental Trauma, especially with deprivation. Developmental trauma is when the trauma and deprivation happen in childhood and have an ongoing effect developmentally. This can be physical, sexual, or relational abuse. It can also be deprivation, where the wound isn’t what happened but what didn’t happen. When there wasn’t enough care, comfort, attention, or protection, our minds filled in the gaps. We created inner caregivers, helpers, protectors as inner structures that gave us what the outside world couldn’t. Dissociation became the space where needs could still be met, even when reality offered none.

How Dissociation Works

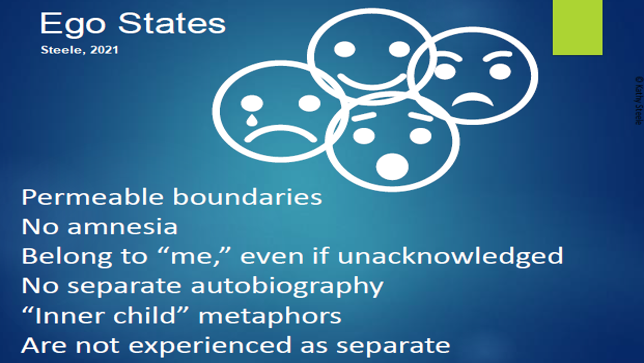

Dissociation is not a choice or a behavior. It is a neurobiological response. It’s quite normal, and everyone experiences it to some degree. We may refer to these as “ego states” when we think about, for example, the part of me that is a parent and the part of me that is a student and the part of me that likes to play outside.

When someone grows up with trauma and deprivation, the combination of the brain’s effort at focusing on survival with the neurobiological impact causes further distinction from those states. Over time, these states become reinforced roles children and teenagers are expected to fulfill, further solidifying them as actual distinct personalities.

Think of it as the nervous system’s emergency plan. When pain or fear can’t be escaped, the experience is divided into separate parts: one may hold the memory, another the emotion, another the day-to-day functioning. Over time, those parts can become distinct, each carrying pieces of life that once felt too much to hold all at once.

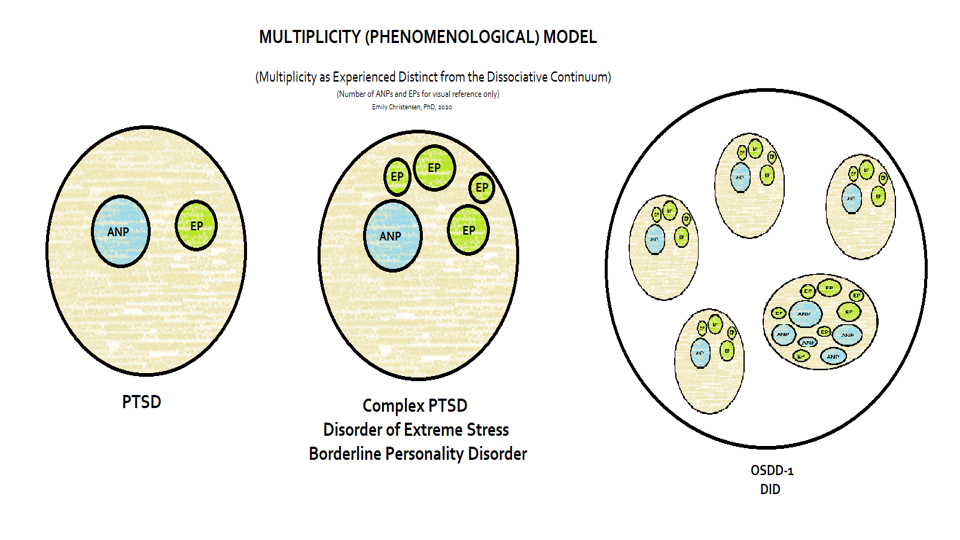

Another way of looking at it is that there are parts of us that handle daily living tasks: going to school, doing homework, parenting, managing relationships, and functioning at work. These are sometimes referred to as “apparently normal personalities” (or “parts”). We refer to this as an “ANP”.

Other parts of us may remember hard things from childhood, or contain sadness, or express rage. These are sometimes referred to as “emotional personalities” (or “parts”). We refer to this as an “EP”.

When someone has gone through a one-time trauma, they may have a distinct ANP who is still managing everyday life, while another part of them is acting as an EP dealing with the trauma.

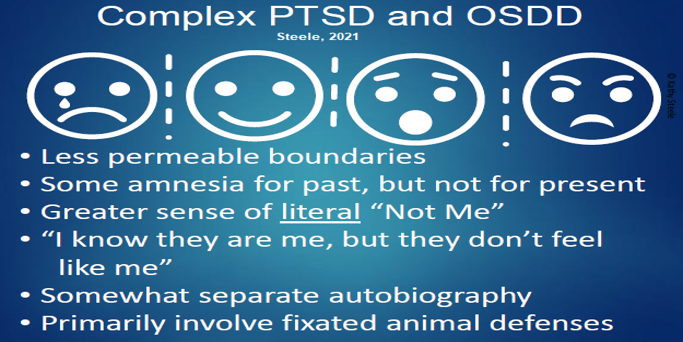

On the other hand, someone who grows up with chronic, relational, and ongoing trauma may have CPTSD. In this kind of experience, they may have an ANP who functions really well in life, but several EP’s because they have been through so much growing up.

With a great deal of trauma and deprivation and no intervention or support for the child as they grow up, and lots of repeated traumas or different caregivers and attachment disruptions, the person may have a number of personalities who each themselves may have more than one ANP or EP.

What Dissociation Feels Like

People often describe it as:

Feeling far away or “not in my body.”

Watching life from a distance, like through a foggy window.

Losing time or missing parts of the day.

Noticing that different “parts” of themselves think or feel differently.

These are not signs of brokenness. They are signs of survival.

Healing Dissociation

Healing means getting to safety physically and emotionally, and then also learning that it’s safe to stay there: to be present, to connect, to belong inside our own lives again. It’s not about forcing memories or breaking down walls. As we experience safety and stability, that happens naturally. We re-gain awareness of and access to ourselves. Through compassion, relational therapy, and gentle internal connection, the system can begin to trust each other and work together differently.

The System Speak Podcast about complex trauma and dissociation is a helpful resource to listen for more information.

The Science of Dissociation

The Nervous System and Threat Response

Under threat, the body mobilizes through the sympathetic nervous system (fight or flight). But when escape or resistance isn’t possible, like during chronic childhood abuse, neglect, or entrapment, the dorsal vagal branch of the parasympathetic system takes over. This creates a state of freeze, collapse, or dissociation: heart rate slows, emotional awareness blunts, and consciousness detaches from the immediate moment. In this state, the brain essentially says, “If I can’t get away, I’ll go away inside.”

Memory and Brain Function

Neuroimaging and trauma research show that during overwhelming threat:

The amygdala (alarm system) becomes hyperactive.

The hippocampus, which organizes memories in time and context, becomes underactive.

The prefrontal cortex, responsible for reasoning and verbal processing, goes offline.

This imbalance prevents the brain from integrating sensory, emotional, and narrative information. The experience gets bundled and stored in fragments (sensations, images, body memories) without a cohesive story. That fragmentation is the foundation of dissociative symptoms: intrusive flashbacks, lost time, and the sense that “parts” of experience live in separate mental spaces.

Attachment and Internal Division

In the developing brain, dissociation also reflects an attachment conflict. When caregivers are both a source of safety and danger, the child’s system faces an impossible paradox: “I need you, but you hurt me.” To preserve the attachment, the mind divides awareness. One part stays connected and compliant, while another holds the terror, anger, or despair. Repeated over time, these divisions form distinct self-states, each containing different memories, emotions, and functions.

This process underlies the development of complex dissociative structures, including Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID).

Deprivation, Betrayal, and Neural Wiring

Both betrayal trauma (harm from trusted caregivers) and deprivation trauma (absence of essential care) shape the nervous system through repeated dysregulation. Chronic hyperarousal and collapse disrupt the development of:

Integrative neural networks linking emotional and rational processing.

Coherent self-representation across time and context.

Capacity for affect regulation and relational safety.

The brain adapts by compartmentalizing these functions. Each compartment or “part” becomes a specialized response to specific environmental demands, personified. Memory Reconsolidation and Predictive Coding Models suggest that dissociation interrupts the integration of new information, preserving separate “maps” of self and reality to prevent overwhelming the system.

Recent Research

Dr. A. A. T. Simone Reinders is a leading neuroscientist in the field of pathological dissociation whose work has helped bridge lived experience, trauma theory, and brain science. Through neuroimaging and functional brain studies, Reinders was among the first to demonstrate that different identity-states in Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) show distinct patterns of brain activation such as when listening to trauma-related autobiographical scripts. Her work has also shown dissociative disorders as specific and unique from other mental health issues. Beyond functional activation, Reinders’ structural brain analyses have identified neuroanatomical markers (e.g. hippocampal morphology) linked to early trauma and dissociative symptoms, supporting the view that DID and PTSD share trauma-related biomarkers.

Dr. Milissa Kaufman is a psychiatrist and trauma researcher whose work bridges clinical care with neuroscience. She serves as Medical Director at the Hill Center for Women and the Adult Outpatient Trauma Clinic at McLean Hospital, and also directs the Dissociative Disorders & Trauma Research Program. Her research focuses especially on women who have experienced childhood trauma, exploring how dissociative symptoms arise in PTSD and Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID). Using multimodal approaches like neuroimaging, psychophysiology, genetics, and cognitive measures, she investigates why some survivors develop dissociation while others don’t, and how dissociative processes affect recovery. Dr. Kaufman is also devoted to translating scientific insight into improved diagnostics, personalized treatment, and reducing stigma around dissociative disorders.

Dr. Lauren Lebois is a cognitive neuroscientist committed to understanding how trauma changes the brain, mind, and body, especially around dissociation. Her NIMH-funded research program at McLean Hospital examines how abnormalities in brain networks, emotion regulation, and cognition relate to dissociative symptoms in PTSD and DID. Lebois’s team uses a mix of neuroimaging, psychophysiology, computational methods, and behavioral studies to map brain signatures of dissociation, identify subtypes, and explore how treatments change those signatures over time. She also works to make these scientific discoveries accessible and clinically meaningful, with the goal of legitimizing people’s lived experience of dissociation and improving care.